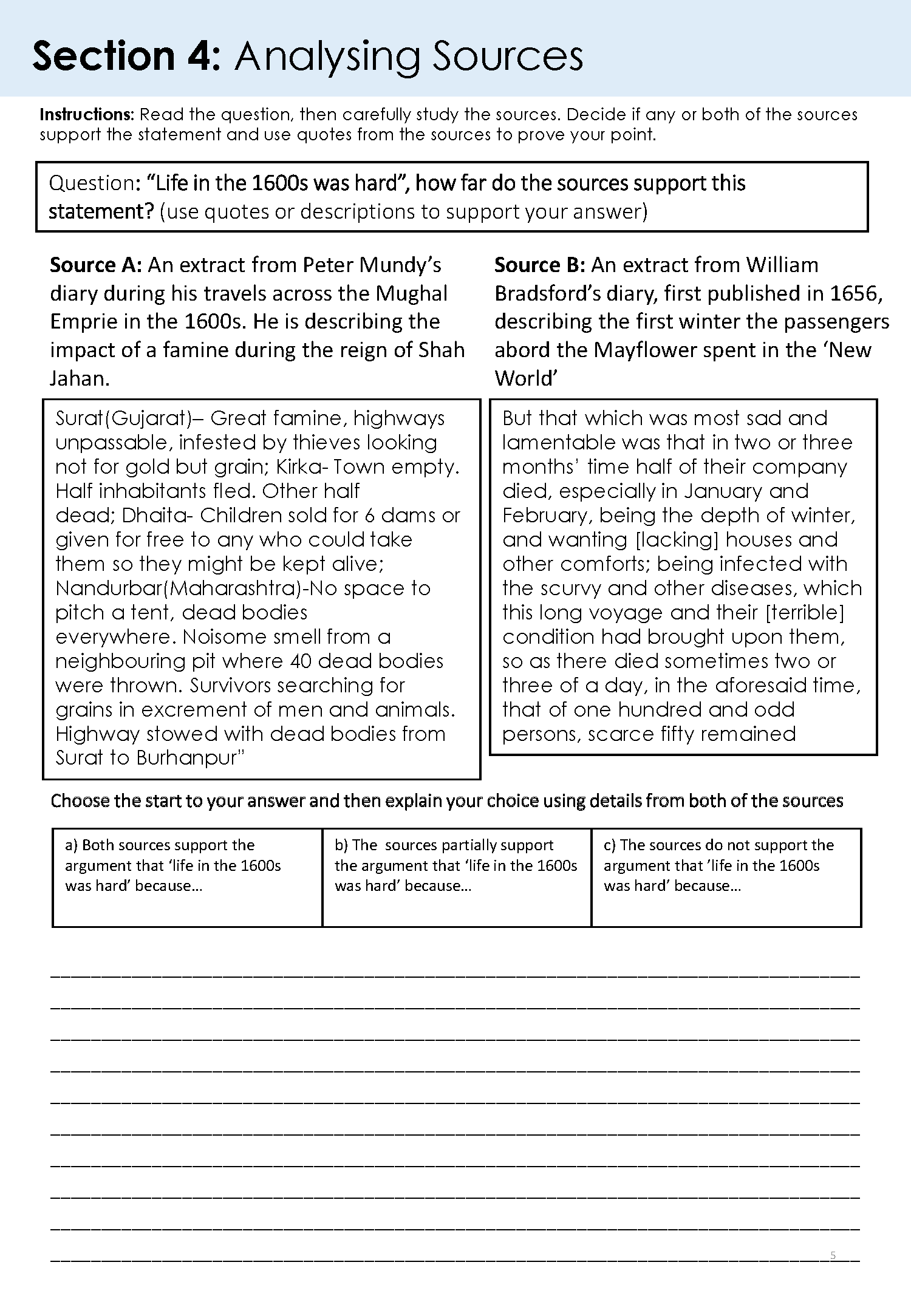

I’m just going to drop this here:

When I first sat down to write this blog I tried to explain how we had tried to solve our assessment dilemma/opportunity/nightmare (delete as appropriate) before showing it, but that was too hard. So I thought I’d show, then tell (So do make sure to look through the assessment before continuing).

A recent episode of Virtually Teachers addressed assessment at KS3. They raised the many issues that assessment presents including the often conflicting purposes influencing assessments, problems of accessibility, questions over format, and the stakes of assessment (high/low/formative/summative). There was also a great thread on twitter addressing assessment (now seemingly lost in the ether…) where a commentator suggested that any time spent assessing had to be carefully weighed up against spending more time teaching, and that, therefore, assessments should serve a particular curricula purpose, alongside any data/reporting requirements.

The assessment you have (hopefully) explored above is our attempt to meet the particular confluence of purposes imposed on and desired by the trust History team. And it’s very important to be clear that this style of assessment, alongside the actually content, might not suit other history curriculums (or Curricula if you’re one of those Latin speakers). It’s tailored to our curriculum, and still needs a lot of work. Right, disclaimers aside, what on earth were we thinking?

Influences

The ideas in the assessment are by no means all our own. A good starting point for thinking about KS3 assessment can be found below:

Our assessment draws on Counsell’s example (which I believe was actually first proposed by Michael Fordham) and the principles behind it, but there are a number of other key other key influences as well:

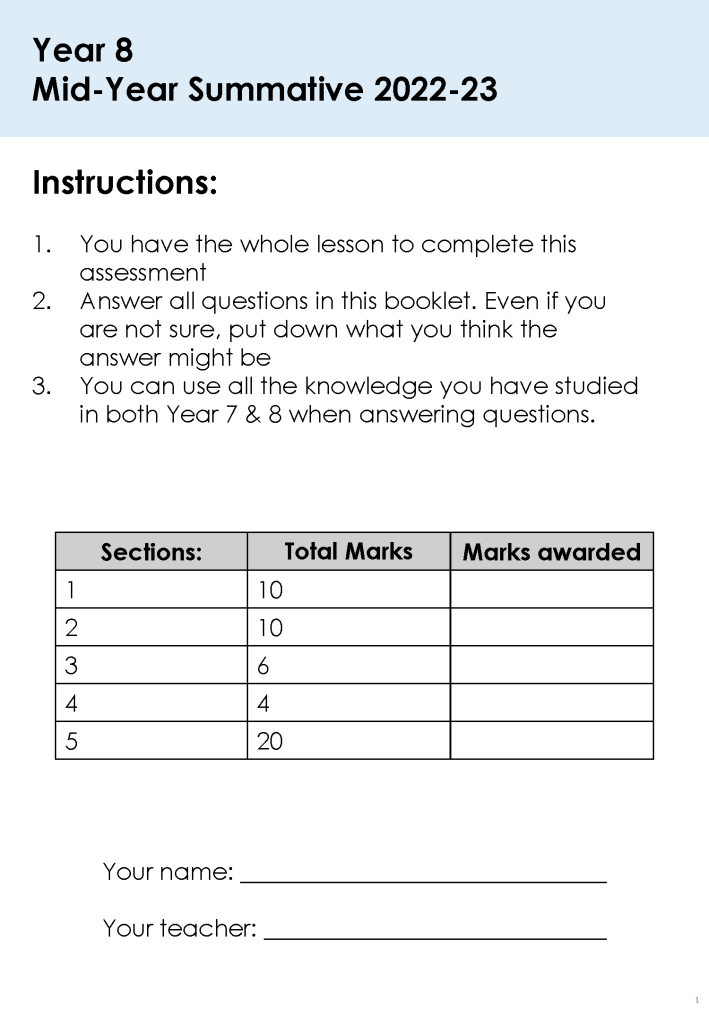

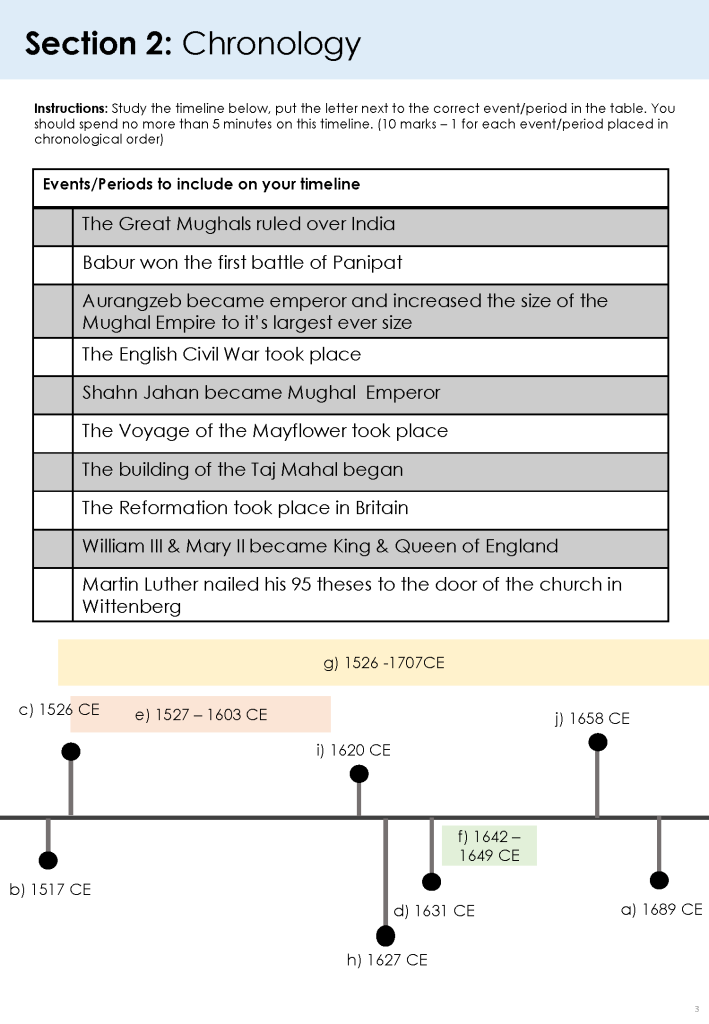

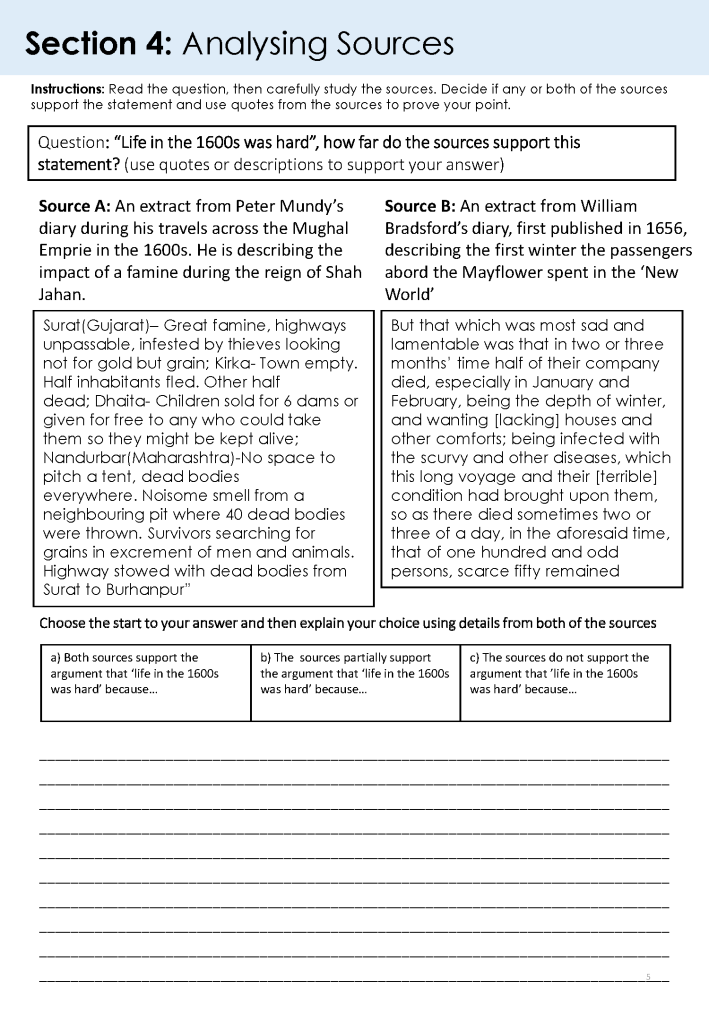

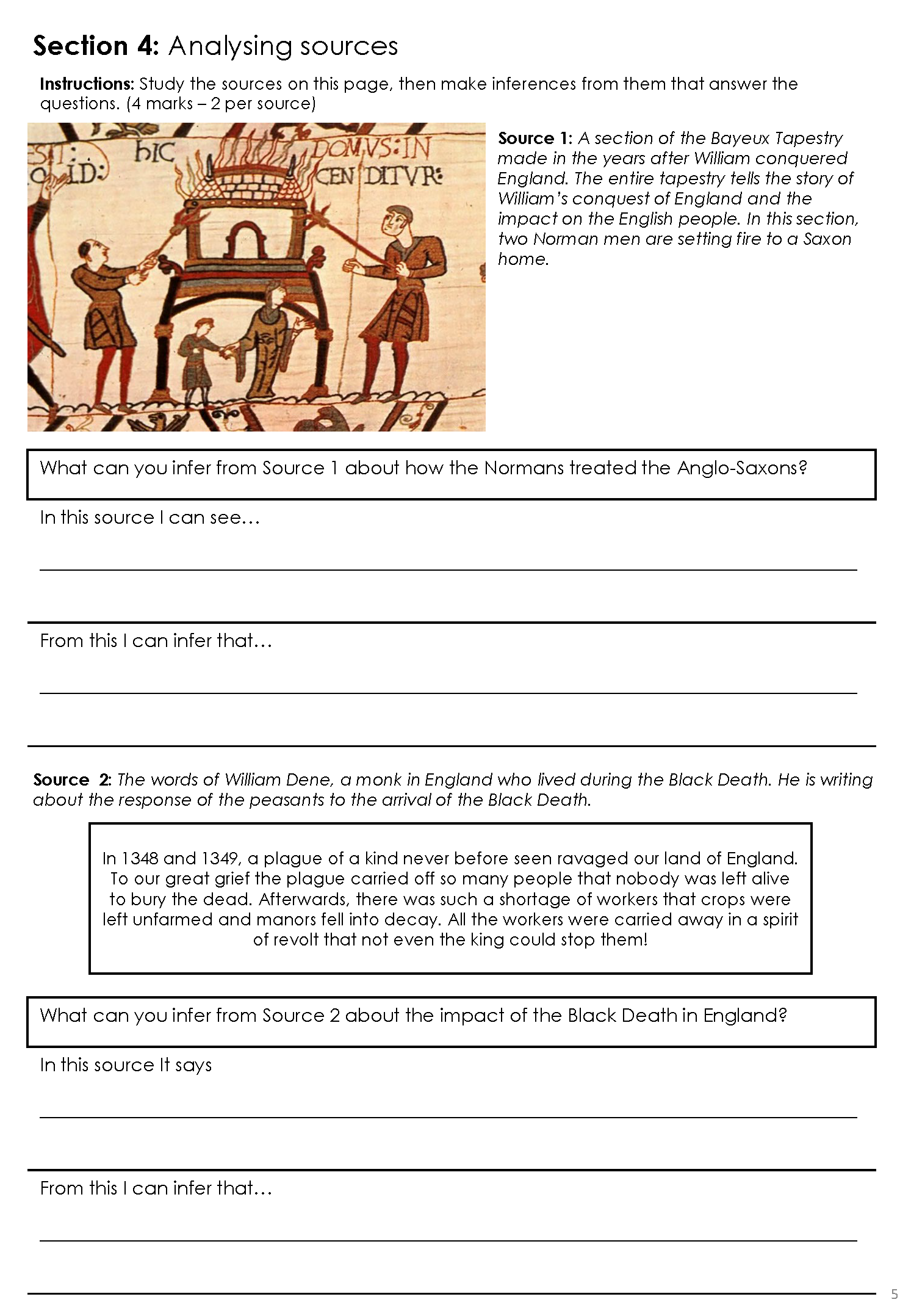

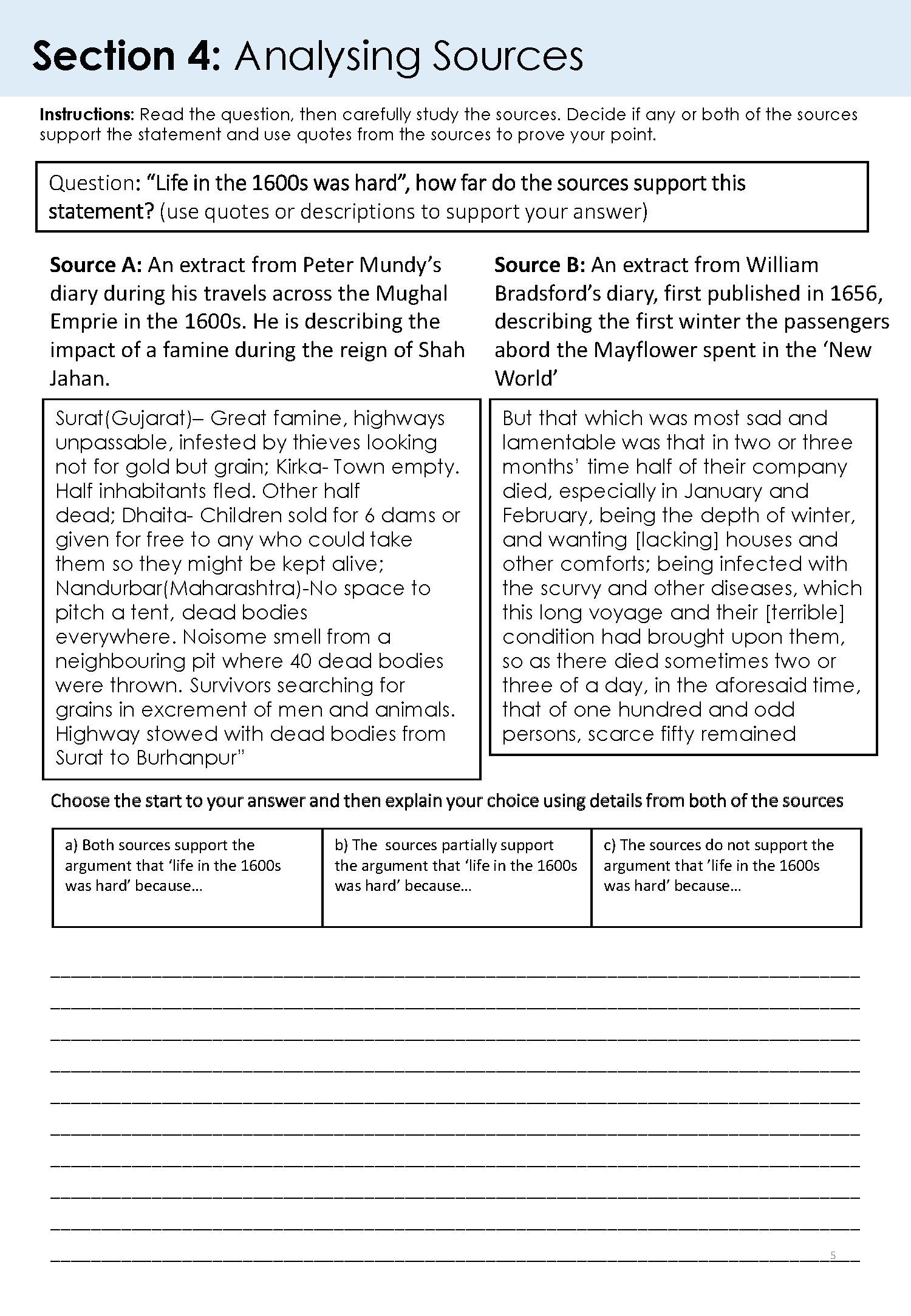

Mixed constitution, from the work of Hammond & Counsell (an overview of which can be found here) – Much like Counsell’s example , our assessment has numerous sections to it, assessing different aspects of historical knowledge and thought in different ways. Our’s includes MCQs, timelines, maps (we think it’s important that students can situate their historical knowledge geographically as well as chronologically to help make it more meaningful), source analysis and essay writing. Now, the mixed constitution idea is not just meant to be part of one assessment, and should also be a feature of regular low stakes testing, but in our high-stakes assessment it is used to assess the aspects of historical knowledge we’ve tried to give weight to in our curriculum, and reinforce the value assigned to them. Further value is then assigned through the marks available, with the most for any single section being awarded for writing an extended historical argument.

Residual Knowledge, again from Counsell but with a great blog from Jonnie Grande that really helps elucidate the idea – We’ve deliberately tried to design the multiple choice questions to test broad takeaways (intended residual knowledge from enquiries) rather than specific facts related any one enquiry. We didn’t want these MCQs to be testing whether students had revised a specific part of a knowledge organiser, but rather what they had grasped and could remember about events/periods/people/groups. What counts as residual knowledge depends on what you’ve taught though. You could put all the correct answers from the MCQs in some sort of revision material, but that wouldn’t achieve the purpose we set for this assessment. The style of some of the MCQs also came out a discussion with Jonnie, with the idea of who was right or wrong when making certain statements something I hadn’t considered using for history before.

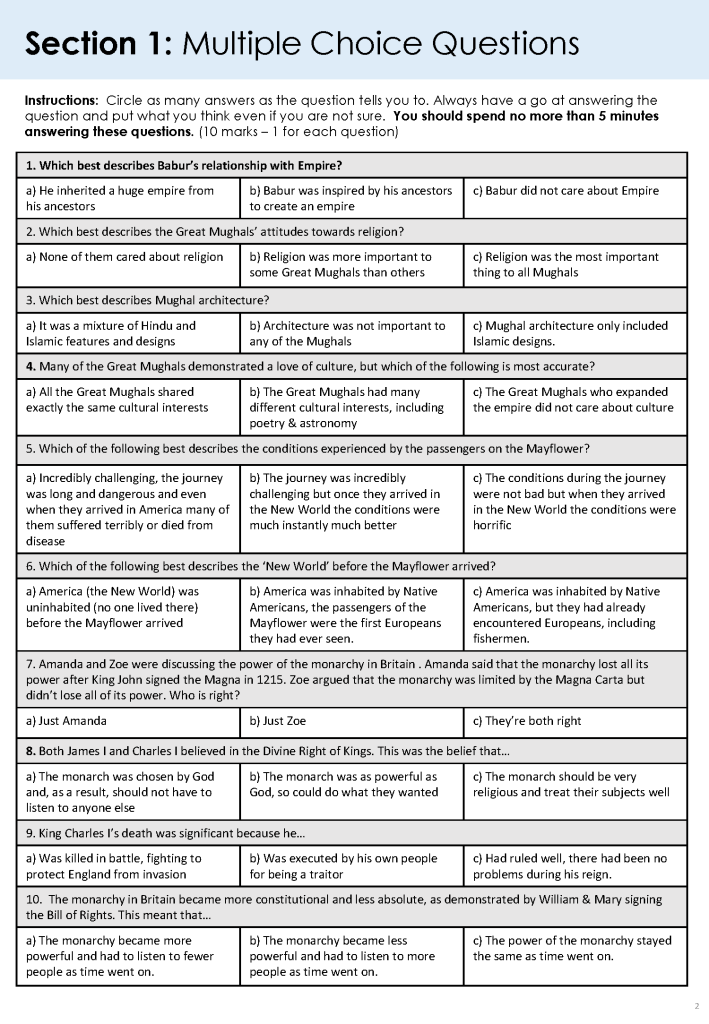

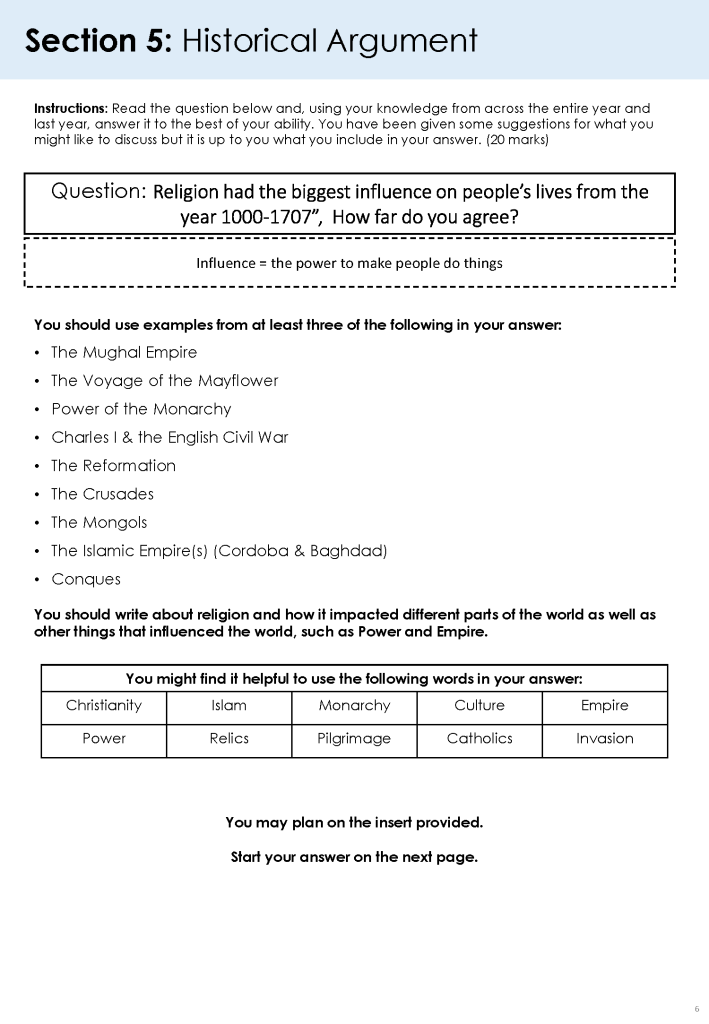

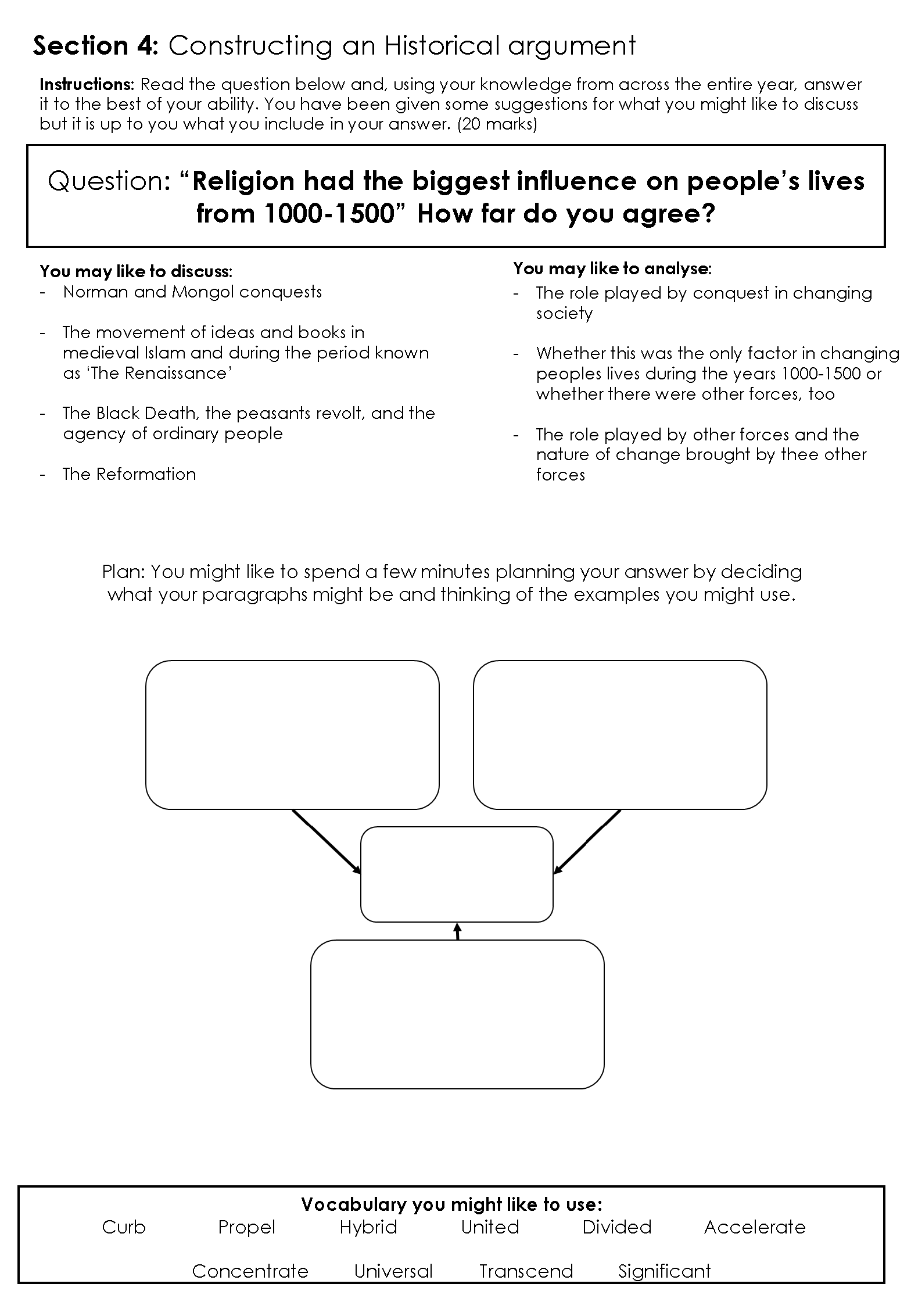

The Curriculum is the Progression Model, Counsell (very hard to avoid Christine’s influence) & Fordham, who has a post specifically about cumulative assessment – This was a big bugbear of mine. End of year assessments that didn’t actually assess much of the year, let alone other years. Our assessment format is designed to be cumulative. The MCQs can include content relating to previous years, so can the chronology and geography sections, and with some careful thought most of the substantive domain can be covered (in some way), but where we’ve potentially taken the biggest leap is with the historical argument section (essay writing). The questions posed revolve around one of the big narratives that drive our curriculum (we have focused on power to begin with as it is probably the easiest to grasp, the other two being migration and agency) and the dates span the breadth of the content studied. As the students progress through the curriculum, the time frame expands to allow them to incorporate new content and reconsider their answer (see below)

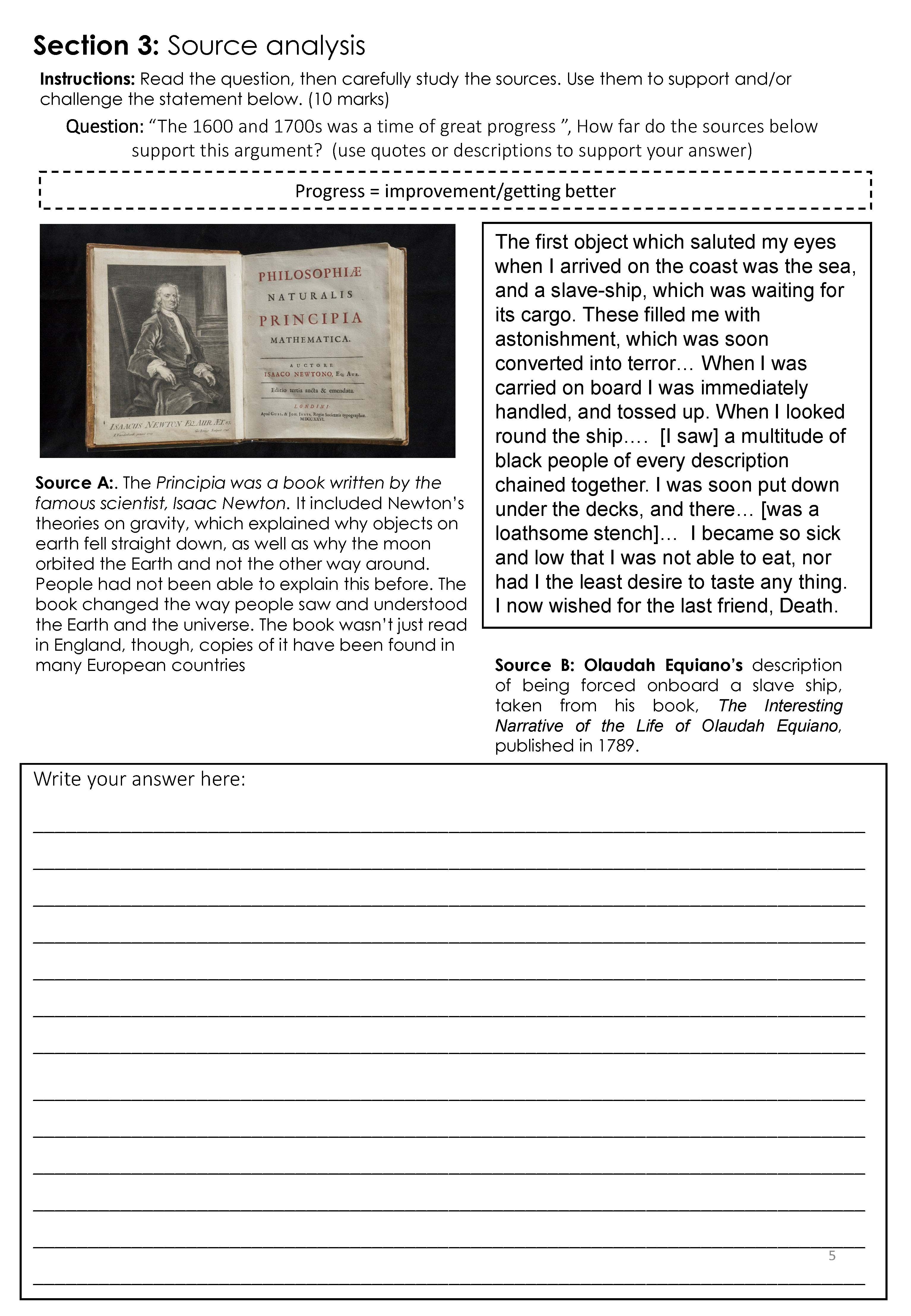

Second Order Concept Progression Models, Alex Ford (see his meaningful models of progression TH article) amongst others. This isn’t obvious from just seeing the Year 8 assessment, but some aspects of the assessments do change as students progress through KS3, it’s not just the increasing domain of substantive knowledge. The source analysis section (see issues below) changes from Year to Year, with year 7 making inferences supported by details, Year 8 cross-referencing sources in relation to a statement and Year 9 reflecting on how the nature, origin and purpose of the sources might have influenced their content (see issues below for further thoughts on this). This sort of follow Alex Ford’s suggested progression model from the article. However, as discussed later, this assessment does not attempt to do this for other second order concepts.

The Geography section also changes in year 9, going from the simpler ‘find [x] on the map’ to having to identify maps (I don’t think there was a specific influence for this but I wanted to try it out).

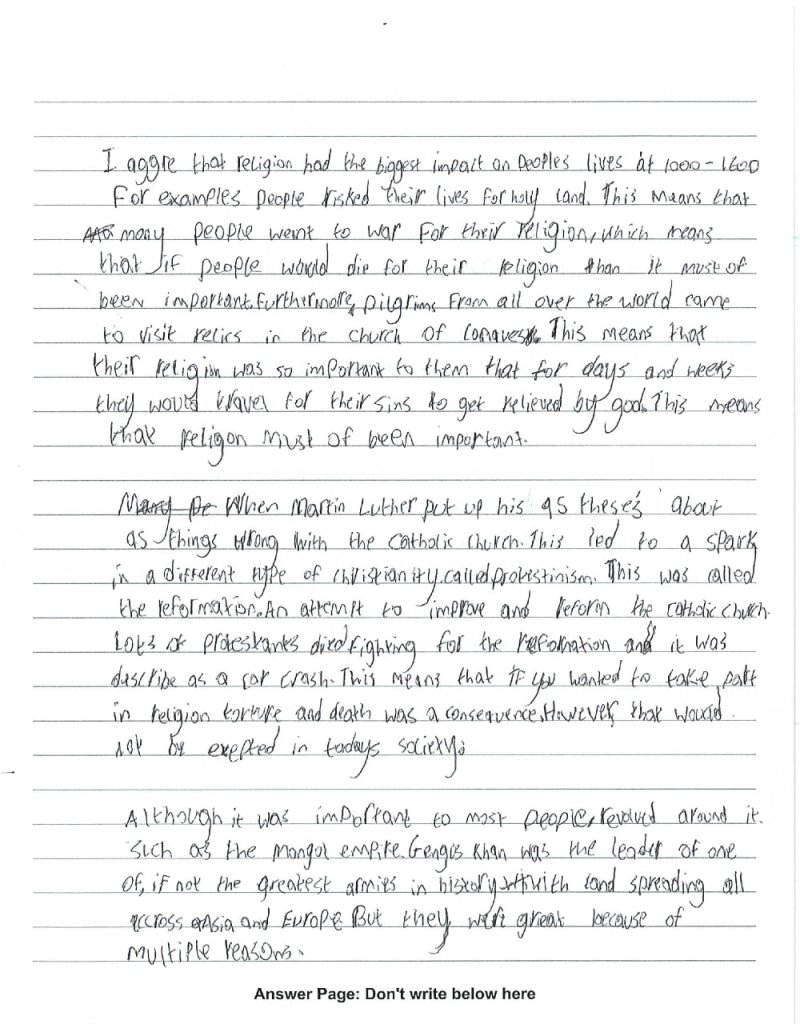

Comparative Marking, Daisy Christodoulou (overview of the idea here) and loads of people who’ve written about how terrible mark schemes are – This is obviously not part of the actual assessment but it did influence the design of the assessment, specifically the historical argument section. (Editors note: this got messy, loads of things started creeping into this influence, so strap in). This influence could also be called ‘Get GCSE out of KS3’. Now a few people have commented that the historical argument question resembles a 16 mark GCSE essay question, with the [statement], how far do you agree? formula. But it is dramatically different. One of the issues with those GCSE questions is they test a very small part of the domain and have an associated mark scheme that can limit marks if certain criteria are judged not to have been met, such as providing knowledge beyond the stimulus points. The use of comparative marking means that if a student doesn’t give a counter-argument to the statement (in this case religion being the biggest influence), then they could still be given credit for writing a great essay that addressed the influence of religion(s) over time (more on this in the potential successes). This type of question is designed to reward students for what they do know, rather than punishing them for what they don’t.

The purpose of using the [statement], how far do you agree? formula goes back to a 2014 article by Michael Fordham in which he suggests that students find it easier to argue if they have something to argue for or against, rather than having to come up with all the potential competing arguments themselves. The question in the example assessment given above could have been “What had the biggest influence on peoples’ lives from 1000-1707? ” but this is potentially harder for students to access and get started with.

[statement], how far do you agree?

Question formula to aid access and promote argument, not just a lazy draw down from GCSE

External Factors

The above aren’t the only influences guiding the nature of the assessment though. As part of a trust there were certain guidelines put in place that these assessments had to conform to, including being able to be completed in a single lesson. This was also a reason for asking one broad question, as the strict time limit meant there would not be enough time to answer more questions, let alone questions deliberately designed to assess each second order concept (I’ll talk more about this in the issues section below). The open nature of the historical argument question also tried to ensure that all students in all schools across the trust could answer the question even if the content they had studied differed, (We’ve moved/are moving to a central curriculum but schools still have different allocations of hours for history and there’s room for contextualising the curriculum) and it was important they answered the same question here as one of the many purposes of this assessment is to be able to complete cross-trust analysis. So it wasn’t all idealistic history teaching driving this assessment’s creation. There were many purposes at play!

Potential Successes

I want to reiterate that we’re still in the infancy of experimentation with these assessments. They are sat at the end of each Year, with the potential for one more assessment window mid-year, so any successes are based on a very small sample size and it doesn’t mean we’ve seen the same across every school in the trust. However, there do seem to be some upsides:

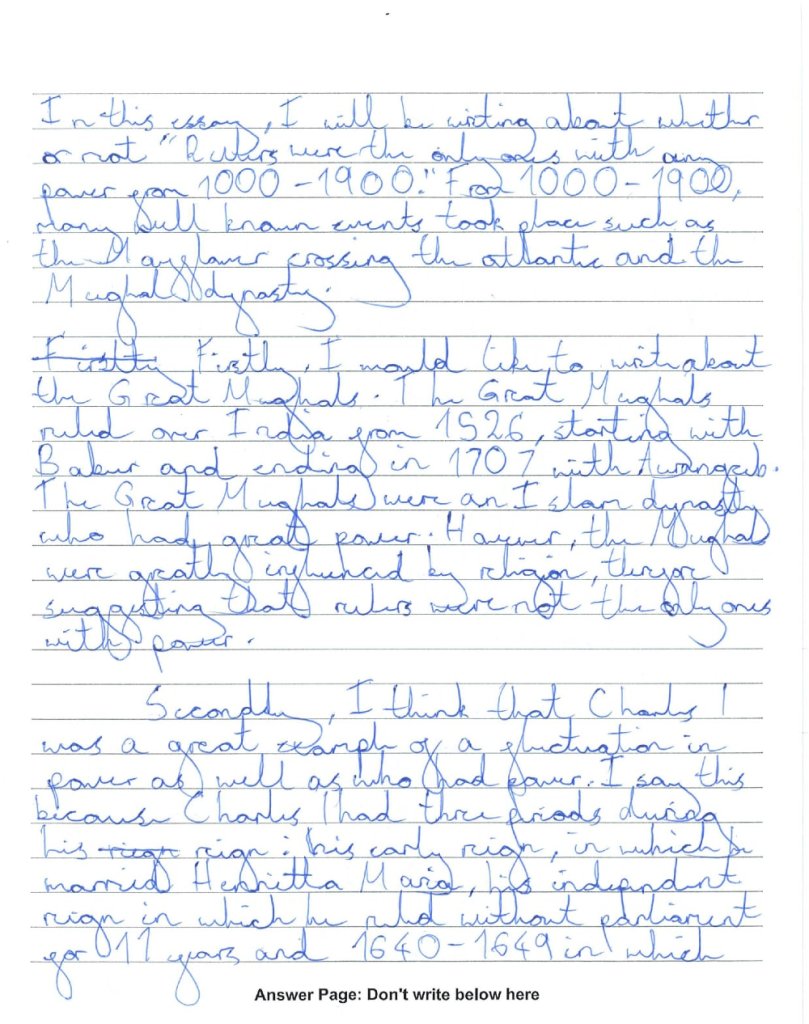

Students demonstrating their cumulative knowledge: I was genuinely impressed by how many students were able to purposefully deploy examples from across the year in their essays, not just relying on knowledge from one enquiry, and how they brought different strands together to compare and contrast. This style of question is something that I don’t think I engaged with until university but many of my students seemed both eager to and capable of wrestling with it. Read the selection below for a flavour of what students were able to achieve. The success of drawing their knowledge together also means that the assessment is serving a curricular purpose, encouraging students to use their knowledge in flexible ways outside of the context in which they learnt it and perhaps see a broader historical narrative than they otherwise might. The year 8 response, for example, contrasts the power of monarchs using the reigns of Charles I and Aurangzeb, two rulers students learnt about in different enquiries, but it also addresses the changing power of Charles I. The Year 7 response contrasts the immense influence of religion on pilgrims travelling to the church at Conques and it’s influence leading to the Reformation with the meritocratic nature of the Mongol Empire. Three different enquiries used to craft an answer to the question.

When completing their mid-year assessment, we simply set the same question they had sat at the end of the previous year but extended the time frame. Again, I was impressed by how much they had remembered from the previous year despite having had a whole summer holiday and a term to potentially forget it. Of course, the other concern is that they just repeat their answers from last year without adding anything (which would still be an impressive amount of recall), but this didn’t seem to be a problem, with students adding more recently acquired knowledge to their answers.

Some evidence of transfer from section to section: Making a paper accessible is difficult when also trying to ensure historical rigour, but we had thought that the sections before students engaged with the historical argument might act as triggers to aid recall and provide some knowledge and/ or sources to use in their essays. This was evident in a small number of essays.

Comparative marking: This was such a joy compared to marking against a mark scheme. You read whole essays, you compare to other whole essays, you aren’t saying one is better than the other because of A01, you are judging them based on their historical merit. This style of marking allows for student eccentricity, it allows for flair, it means that just because one student put in a poor counter-argument about monarchs also having power they don’t automatically score more than the student who showed a deep grasp of religion influencing the lives of people of all stations. And whilst these assessments are designed to be summative, I found that comparative marking gave us as a department a much better grasp of what students had or had not remembered on the whole than we ever had when using mark schemes (The joy I’ve expressed above also came from the process we used but I might write about another time, this blog is already too long and I still haven’t talked about the issues…)

Iteration for access: The example I’ve given is from the second time we’ve sat this style of assessment. One of the things we changed was the use of the multiple choice answer starter for the source question. This wasn’t awarded any marks, but it did seem to help more students answer the source analysis question and helped direct them to write better answers. We also massively streamlined the page with the historical argument, still providing stimulus to indicate that the question required the transfer of knowledge but in a hopefully less extraneous load inducing way than in the first iteration.

No sentence starters: We don’t drill sentence starters. The curriculum time spent preparing for these assessments consists of ensuring students are familiar with what the paper will look like and then working on schema building for the big narratives, such as power. This type of question won’t be accessible for a lot of students if they have never been asked to think in the way the question is asking them to (the examples above were from the first time students had ever attempted to codify their answer to such a question), but doing some brainstorming of who/what they have studied that had power/influence has seemed to be an effective way of preparing students and supports our curricula intent, rather than being a bolted on addition to just serve the assessment.

Chronology: You don’t always want students interacting in timelines in this way (matching dates to events/periods), sometimes you’ll want students to construct them from scratch, for example, but the way we have set them up makes it very easy to mark with no complications over some events/periods being in the right order but some not (We tried the way suggested in Counsell’s example but found marking it a massive headache and data validity for this section poor as a result).

Issues

Lots of these (beyond any mistakes you may have spotted in the assessment):

MCQs: At the moment some of the answers are doing too much, i think it was Dylan Wiliams or Harry Flecther-Wood who advised that the complexity should always be in the question, not the answer. Some of these questions might also be too hard. This iteration of the exam also only really allows for 3 possible answers due to the table format, it would be better to be able to provide more possible answers where appropriate.

Finger-tip knowledge: Just to be clear, there were some students who did not write anything for their essays, we haven’t solved teaching and assessing history with either our new curriculum or this assessment and access is still an issue for some. The other thing that we noticed was a somewhat lack of specific detail in the essays. As Hammond discussed in her TH Article, a lack of finger-tip knowledge can leave answers feeling somewhat fragile, even if the argument is sound. You might have thought this when reading the examples given above. So this is something for us to consider. At the same time, students only had around 30 minutes to complete these essays, when they usually spend a whole lesson completing end products, so we may need to temper expectations. Still, perhaps some more retrieval practice is in order.

Chronology: This is more of a curriculum issue, we just don’t do enough low-stakes chronology testing, so when it comes to the exam students tend to do poorly, potentially encouraging teachers to get students to rote learn timelines (i’m still wrestling with how much of a problem this actually is…). And because the section is assigned 10 marks, we have to put ten events or periods, when you might not actually want/need to put that many and so end up adding obscure things that students only studied once.

Source analysis: This is an odd one. We give prominence to this over any other disciplinary concept (let’s not get in to a debate about whether sources and evidence are a second order concept just now) by giving it it’s own section and leaving out, for example, interpretations. This is a decision we’ve made. I’m not sure it is the right one, but it sort of feels right. Whether the progression we’ve gone for is right is also up for debate. I’ll write another post about my thoughts on progression models in second order concepts, but I wanted to clarify that I don’t think this is the only way you could do this and would love any feedback. A few changes we will be making. Phrasing, the sources don’t support or challenge a statement, they can be used to support or challenge a statement. Maybe a small one but it is a misconception that students (and teachers) can have that sources are evidence rather than that they can be used as evidence. Also, getting rid of ‘Source A’ and ‘Source B’ and referring to them by what they actually are (this is another Michael Fordham influence and something we discussed at the trusts last strategy group meeting. There also isn’t really enough room for the writing, so perhaps the sources need to be printed on a separate sheet/insert.

Speaking of a lack of interpretations, I should probably also address the lack of any direct attempt to assess the grasp of any specific second order concepts. The reason for this is that I simply could not see a way to effectively do this given the restrictions on the assessment. 50 minutes is not enough time to answer a question trying to assess each second order concept individually, and neither do I think that even with two 50 minute assessment windows a year you could do it well. So we haven’t attempted to track or measure any sort of progress across second order concepts (we do intend for students to make progress, though – again, thoughts for another time). Having said that, the answers students have written demonstrate the use of different aspects of second order concepts to help them answer these broad questions, often combining more than one, in line with how historians actually write

Reflections

I’ll be brief. This blog has become a monster as is. My key reflection is that I think we are on the right track, especially with the cumulative aspect of the assessment and the broad conceptual essay question. The ‘joined up’ thinking it requires helps ensure that the assessment serves a curricula purpose as well as reporting one. Comparative marking against exemplar scripts is also a great way to mark history essays. Try it. You will want to burn every mark scheme you have ever used…

We still need to refine, though, and ensure that, without going down the path of drilling sentence starters, our curriculum properly preps students for the kind of thinking required by the assessment.

Right, I think that is enough for now. Please let me know your thoughts on our assessment model and send any suggestions my way!

Leave a comment